Prepare for Launch: Enrichment Strategies for Apache Flink

Sometimes, when we’re getting ready to launch a new Apache Flink job — or even just roll out a major new feature — we run into a familiar problem: we need meaningful data in state before the job can do what we built it to do.

While enrichment is probably the most common example, it’s far from the only one. Any time your pipeline depends on referential data, configuration, metadata, or external context, you’re going to run into some flavor of this challenge. And unfortunately, it’s one that doesn’t always have an obvious or painless solution.

In this post, I’ll walk through a few of the enrichment and bootstrapping patterns I’ve seen (and experimented with) in the wild, along with some of the trade-offs that come with each.

Restating the Problem

Let’s start with a simple example.

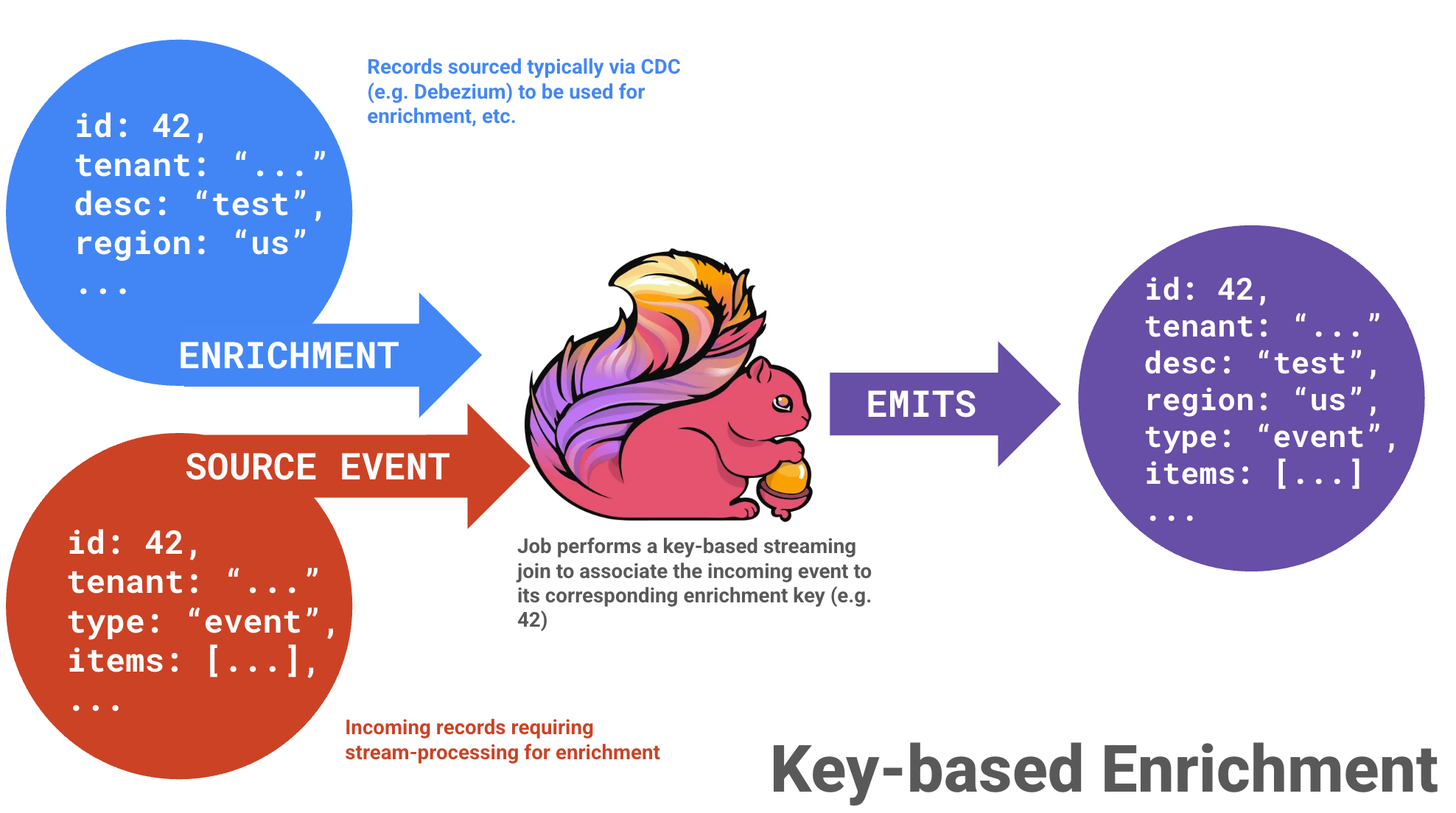

Imagine you want to enrich incoming records using some associated values from your database. This can be accomplished by a key-based streaming join operation (similar to a SQL JOIN but on steroids since everything is moving):

id = 42). The Flink job maintains state for each side and joins records as they arrive, emitting enriched events downstream.This would typically be done by just issuing an external API call when we see the record:

In most cases, this works just fine.

With lower volumes, you issue an API call, enrich the record, maybe cache the result, and move on with your day. Simple, understandable, and easy to reason about.

So far, so good... right?

Then your company’s product goes viral on TikTok or something.

Traffic jumps by 1000x. New identifiers start flooding in. Cache hit rates drop. External calls pile up. Latency climbs. Backpressure follows. And suddenly your nice, tidy enrichment pipeline is very, very much on fire.

Each new identifier now means:

- more database or API calls

- higher latency

- more load on downstream systems

- more operational stress

Crap.

This is usually the point where you realize that “just make an external call” isn’t going to cut it anymore. Now you have to start thinking about alternative strategies — ones that can scale, remain reliable, and not wake someone up at 2am.

Before we dive into those options, it’s worth taking a quick look at the building blocks that tend to show up in these systems.

Common Pieces to the Puzzle

Before getting into specific strategies, it’s worth calling out a few building blocks that tend to show up in most real-world enrichment pipelines.

If you’ve worked with Flink before, none of this will be surprising — but these components show up often enough that they’re worth naming explicitly.

Change Data Capture (CDC)

Usually something like Debezium, as it's considered one of the defacto standards as far as this goes.

A CDC connector monitors your source system (typically a database) and continuously publishes change events into Kafka. Many connectors can also emit an initial snapshot, giving you a full copy of the current dataset (spoiler alert: one of the patterns focuses on this).

In enrichment-heavy pipelines, CDC is typically going to act as our truth conduit for getting data into our streaming pipeline.

State Processor API

The State Processor API is Flink’s “power tool” for working with state outside of a running job.

It allows you to:

- read existing savepoints

- modify operator state

- generate new savepoints

In a nutshell, it provides us a way to seed or pre-populate the enrichment state (or any other state) before a job ever starts processing live traffic. It’s incredibly useful (and can be easy to misuse), which is why it tends to show up in more advanced pipelines.

Enrichment Strategies

A few of the common solutions that I've seen on this front can be broken into three major categories, which may or may not be options depending on your use case, consistency requirements, etc.

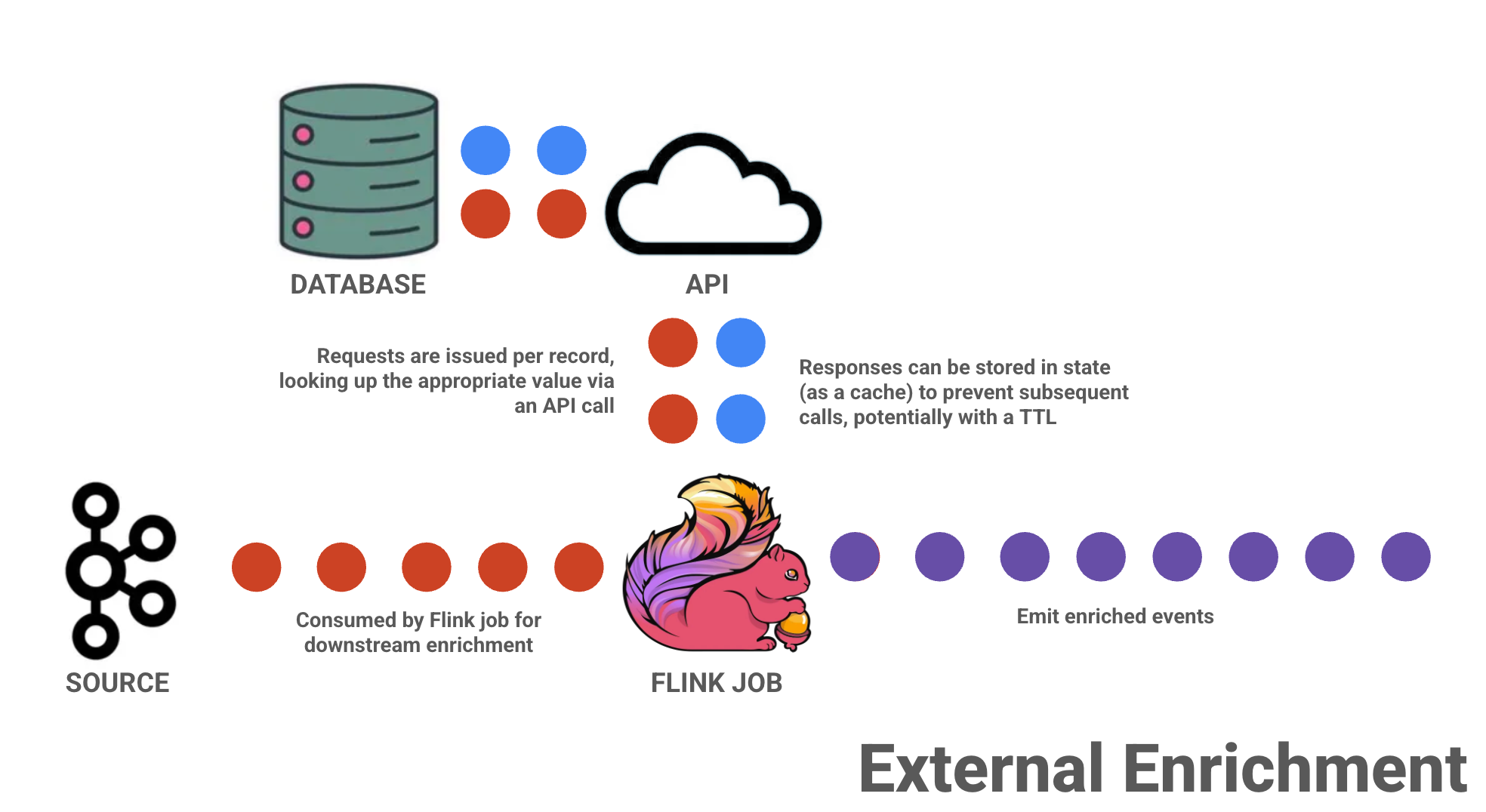

External Enrichment

As mentioned earlier, if you are dealing with lower-volumes of data, it's very likely that simply issuing a request against an external source (e.g., database, API, etc.) is probably a totally fine option.

This approach is perfect for low-volume scenarios and those that can afford some staleness in data (if you are leveraging state as a cache with a TTL). It can start to falter at scale, so it's important to be mindful if volumes begin to grow unexpectedly.

Gradual Enrichment

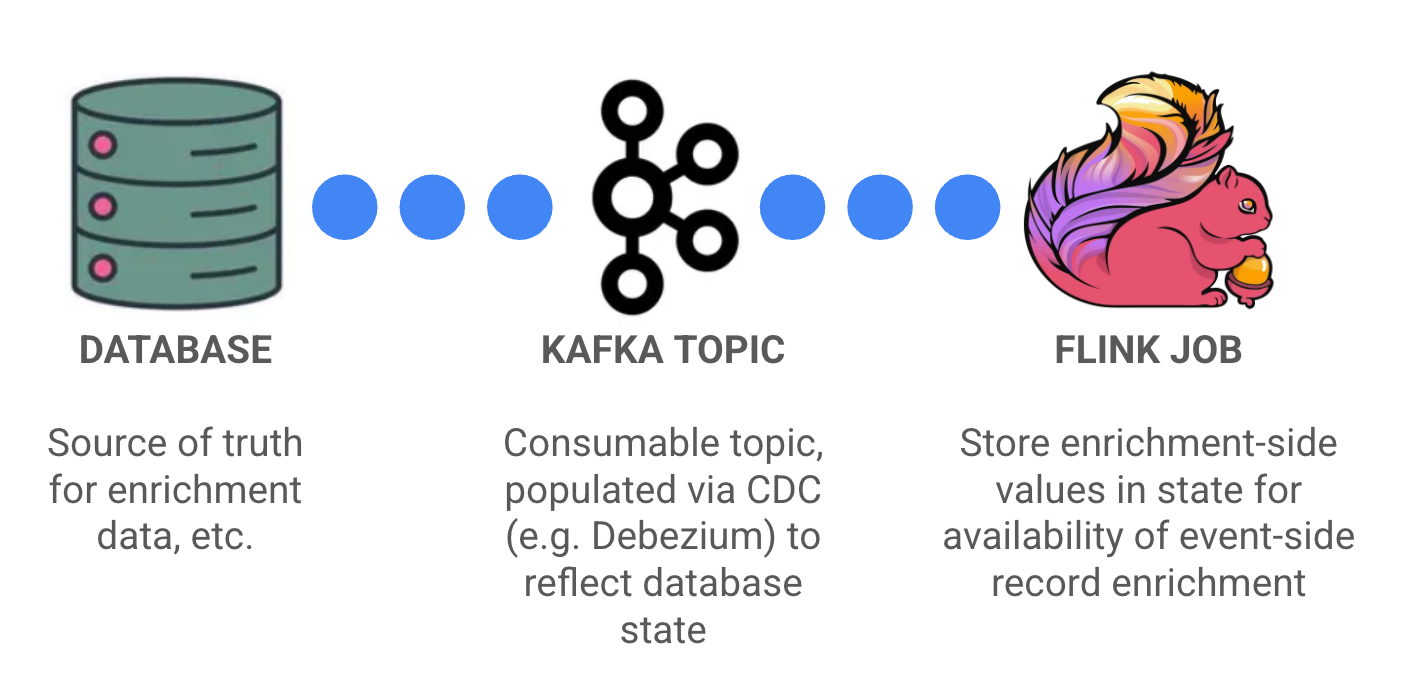

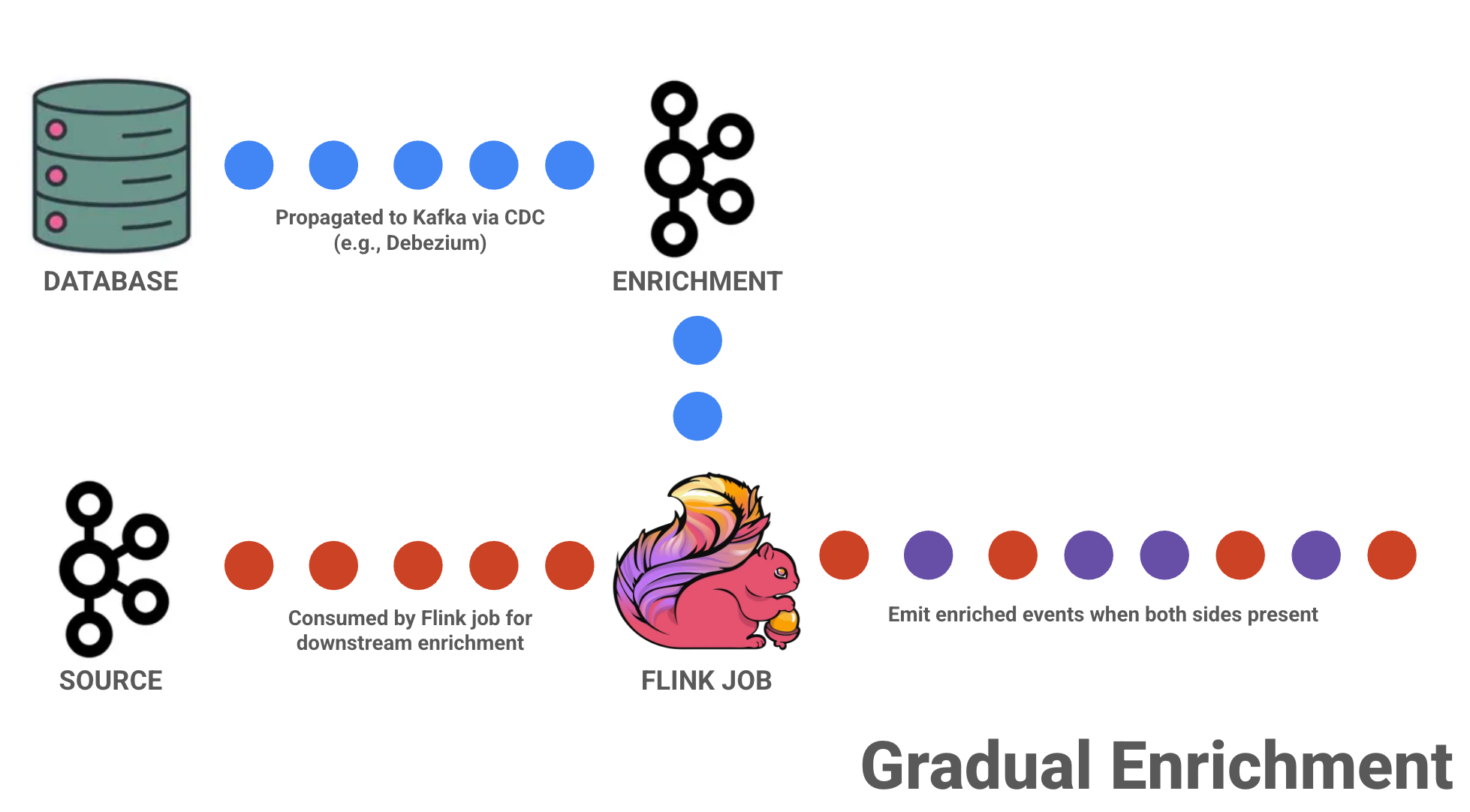

Another option — especially once per-record external calls stop scaling — is to move toward a gradual enrichment pattern.

Instead of issuing lookups on demand, this approach introduces a change-data-capture (CDC) stream that continuously ingests enrichment-side data and stores it in Flink state for future use.

Over time, your enrichment cache “fills in” organically. You’re essentially pre-performing the join, so that when source events arrive, the associated values are already there.

Early on, many keys may be missing and some events will be only partially enriched. As more CDC records arrive and state fills in, enrichment becomes more complete and cache hit rates improve. Eventually, assuming the enrichment stream is comprehensive, the system converges.

Gradual enrichment is often the simplest state-based enrichment strategy to implement, but it comes with two important caveats:

- It provides only eventual consistency.

- If an event arrives before its corresponding enrichment record has been ingested, it won’t be fully enriched. That may be perfectly acceptable in some systems — and completely unacceptable in others.

- It introduces new infrastructure dependencies.

- You now need a CDC pipeline, one or more Kafka topics, and operational ownership of that data flow. All of that is manageable, but it’s still real complexity.

With all of that being said, this is a very practical strategy if you can tolerate eventual consistency or potential missing enrichments (typically while the enrichment keys are being populated).

Two-Phase Bootstrapping

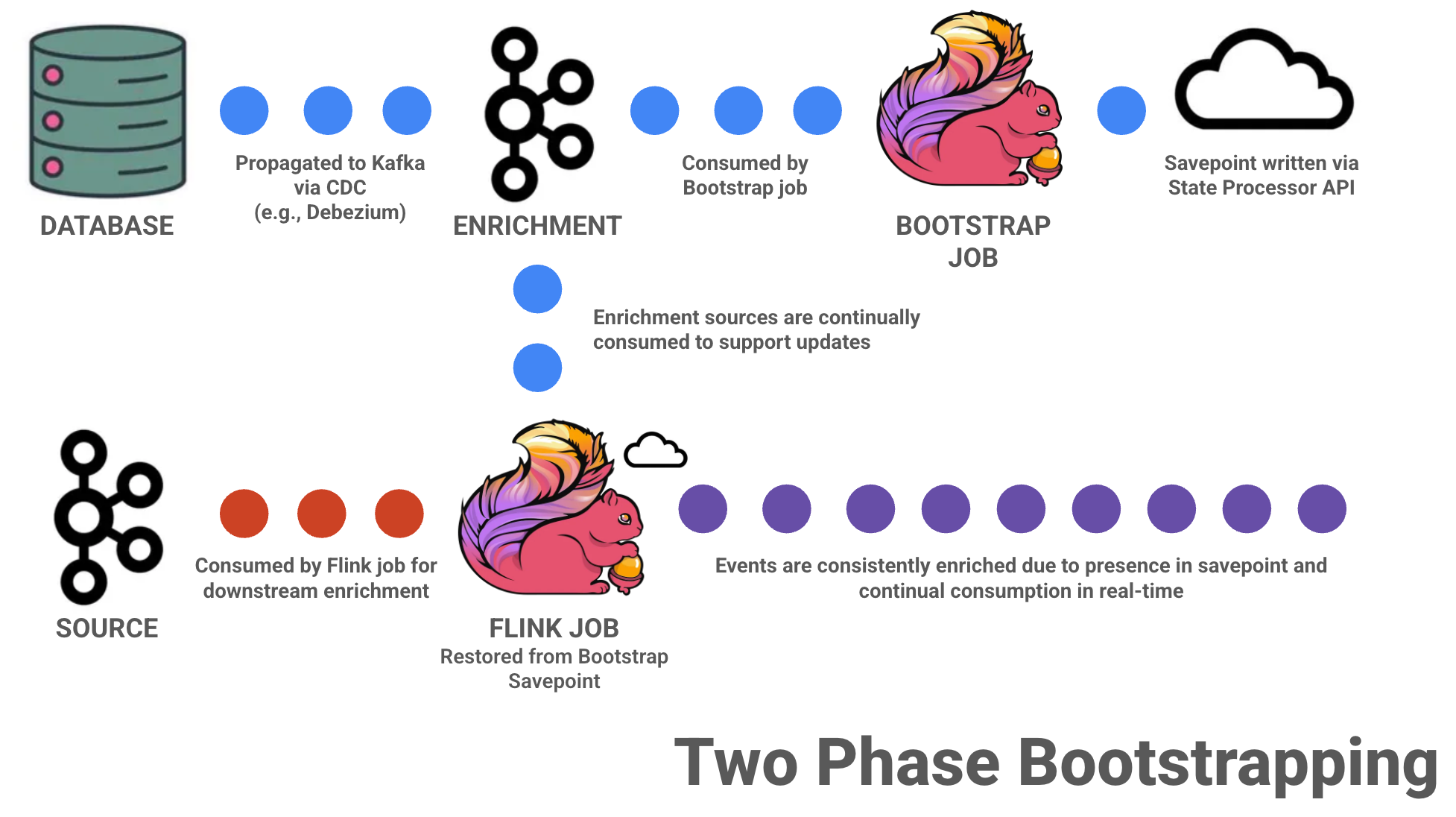

If you need stronger consistency guarantees, are dealing with extremely large enrichment state, or are seeing instability when consuming enrichment and source data at the same time, a two-phase bootstrapping approach is often worth considering.

This is usually the point where eventual consistency stops being acceptable, and you need your job to start in a “fully warmed up” state.

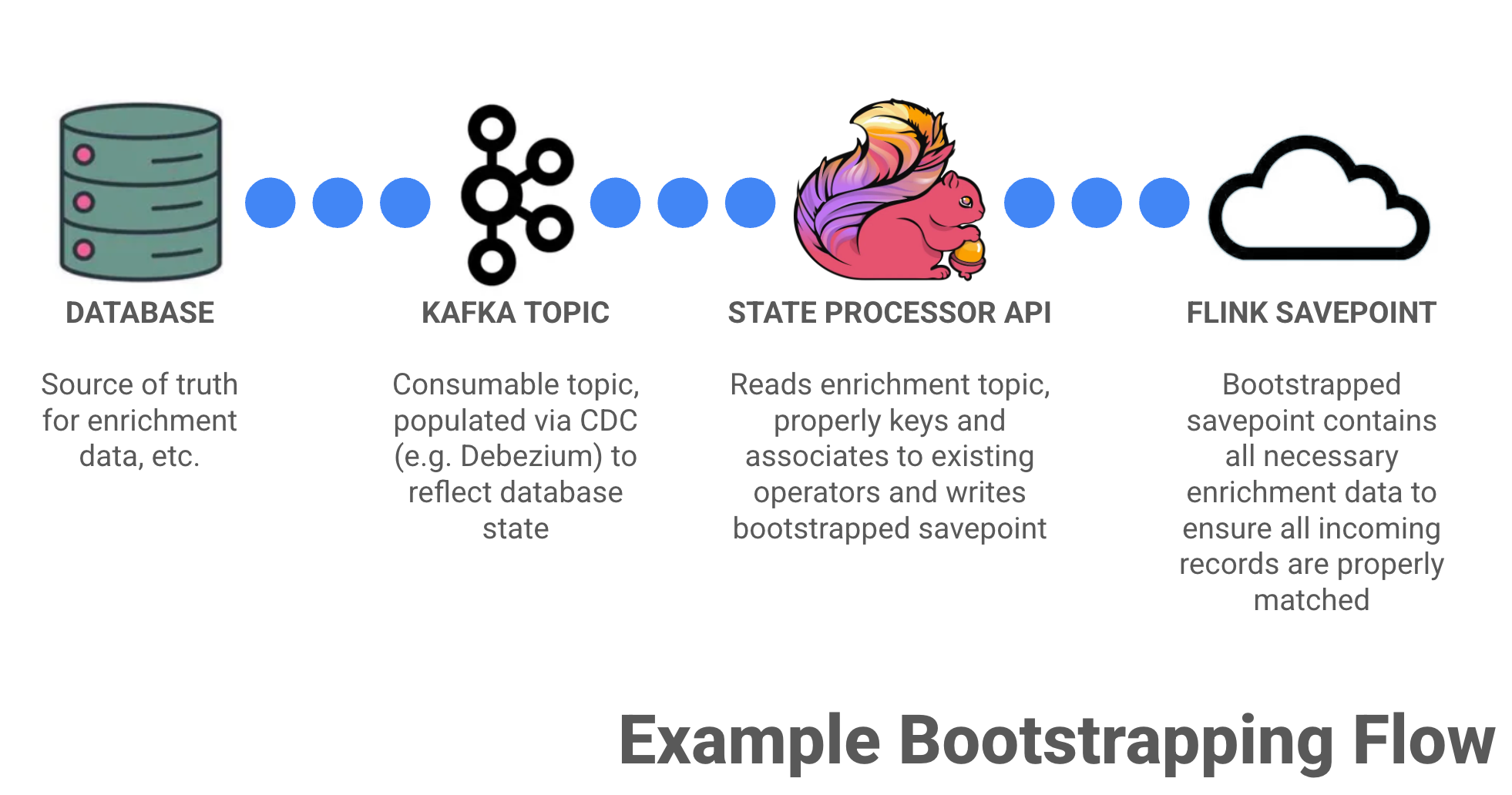

This strategy builds on gradual enrichment but leans much more heavily on orchestration. Instead of letting state fill in over time, you explicitly populate it up front before processing live traffic through a bootstrapping process.

In practice, this typically involves running a dedicated bootstrap job whose only responsibility is to read the full enrichment dataset and materialize it into a Flink savepoint (this doesn't have to be a dedicated job as there's quite a few ways to slice this apple).

That job consumes a CDC-backed Kafka topic containing a snapshot of your enrichment source, keys records consistently with the main job, builds operator state, and writes out a reusable savepoint.

Once that completes, the primary job is started from that savepoint and begins processing live events.

From that point on, the application behaves like a normal streaming job. All incoming records can be enriched immediately, and ongoing CDC updates keep state in sync with the underlying source.

Two-phase bootstrapping requires careful coordination around snapshot timing, savepoint creation, job restarts, and failure handling. It often involves scripting or automation to ensure the handoff between phases happens cleanly.

The upside is that this work happens outside the critical path, giving you the option to tune the bootstrap job independently for throughput, focus on loading state as quickly as possible, and only switch to live processing once everything is ready. I'd highly recommend leveraging parallelism as much as possible and potentially dedicating more resources to ensure this is a quick, reliable process

For systems where correctness is non-negotiable and startup delays are acceptable, this added complexity is often a reasonable price to pay.

Gating Enrichment

One other pattern that’s worth mentioning is gated enrichment.

This concept sits somewhere between gradual enrichment and two-phase bootstrapping. The job consumes enrichment data and source events at the same time, but delays emitting results until enrichment state reaches some defined “ready” condition — often tied to CDC snapshot completion or some other similar signal.

In practice, this usually involves buffering incoming events in state until the gate opens, at which point processing proceeds normally.

I’ll be honest: I’ve seen this approach discussed far more often than I’ve seen it successfully implemented in production which is why you aren't going to get a fancy diagram like the others for it 😄.

There seems to be quite a bit of complexity and trickiness involved in terms of getting the gating conditions right, managing buffer growth, and handling slow snapshots. I'd imagine when it works, it could provide strong correctness guarantees without full two-phase orchestration.

If neither gradual enrichment nor full bootstrapping feels like a good fit, this is another option worth exploring — just go in with your eyes open.